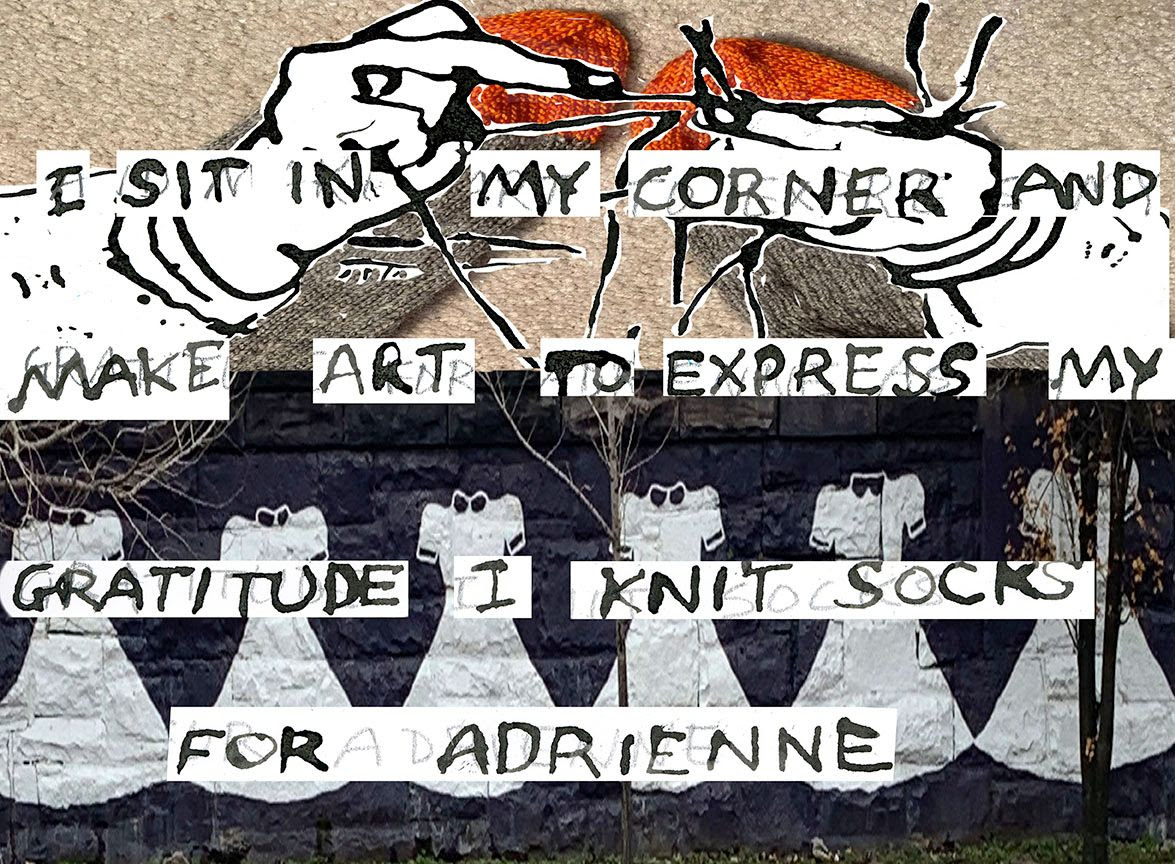

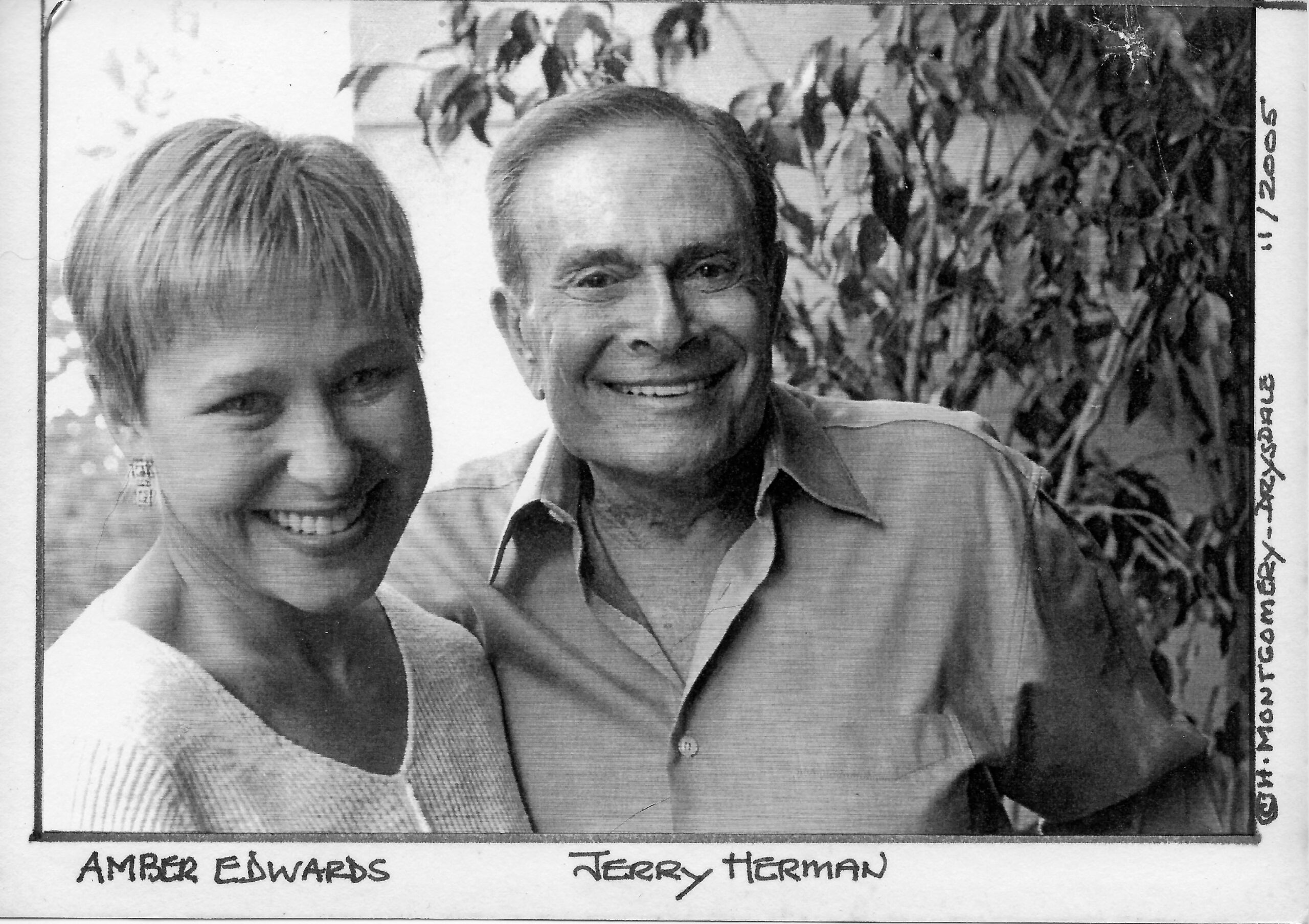

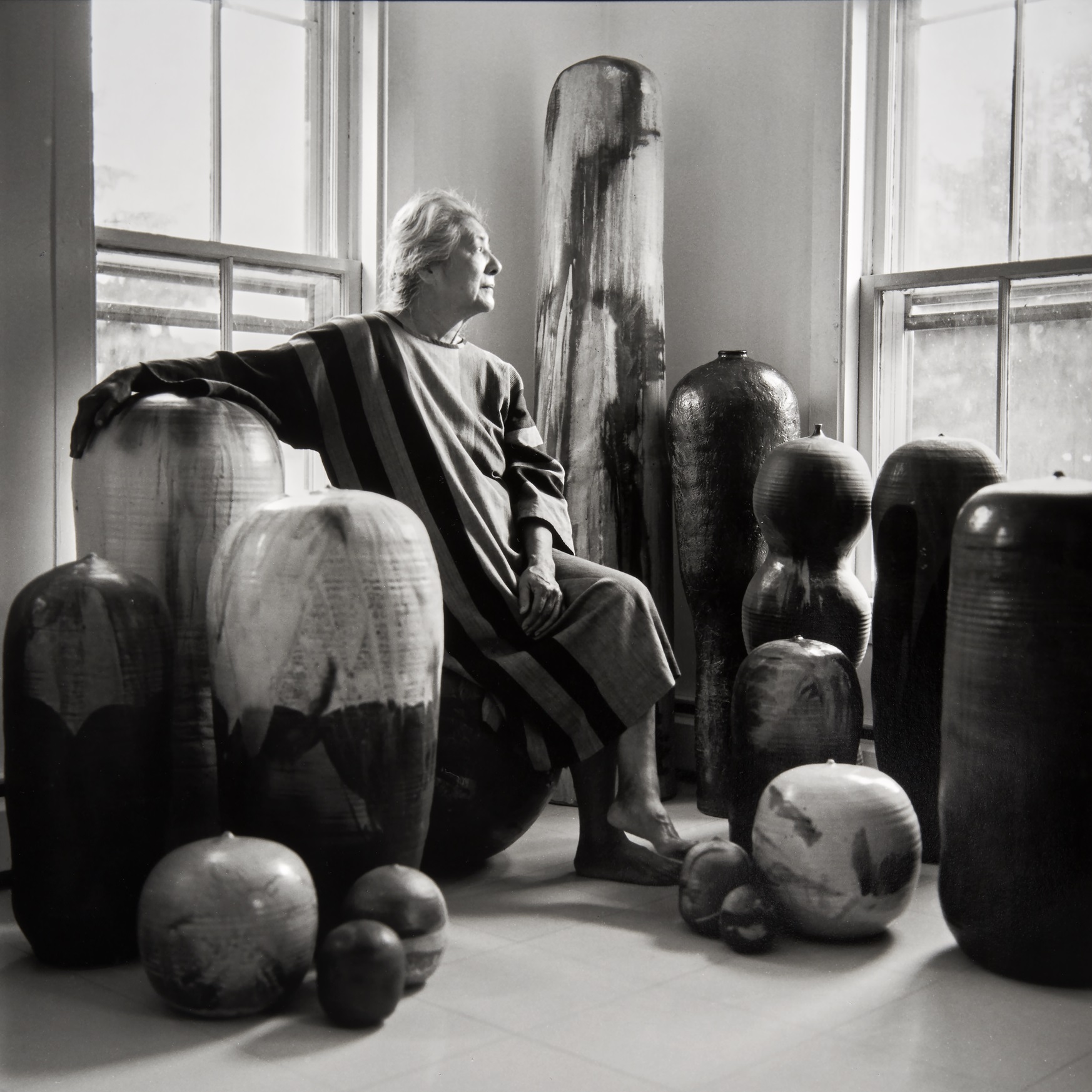

Artist and historian Nell Painter wrote this essay to accompany

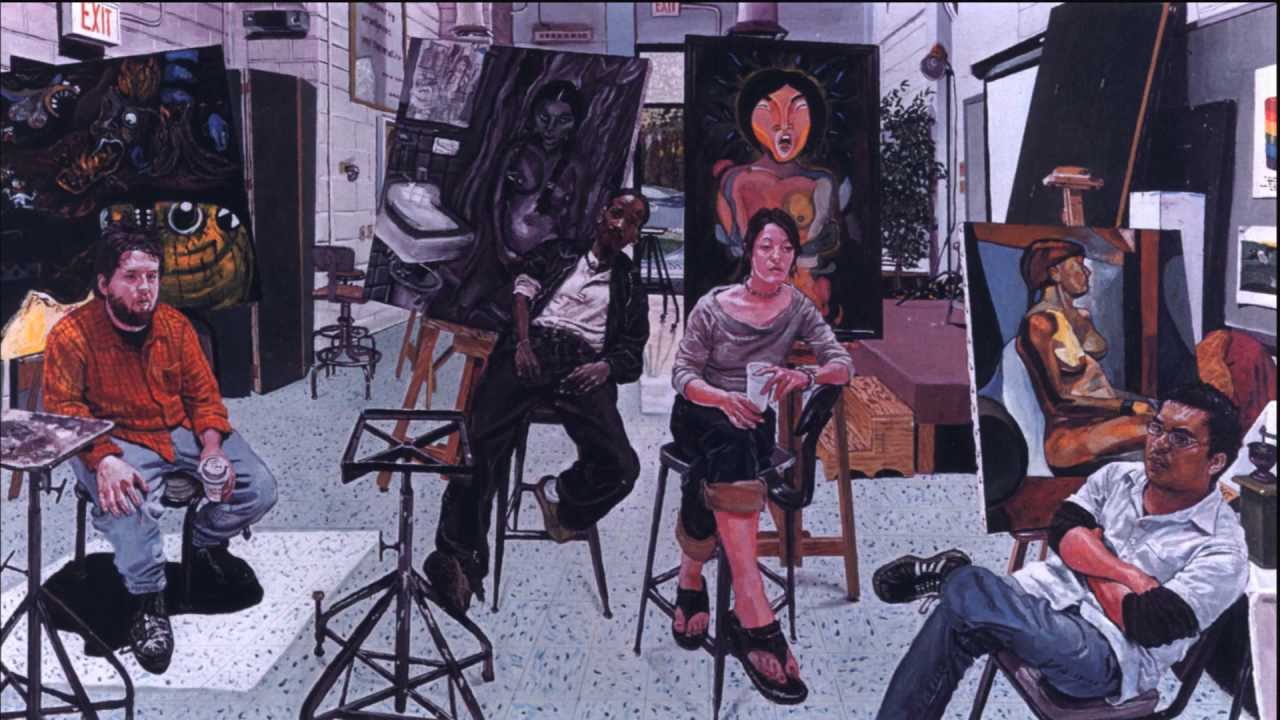

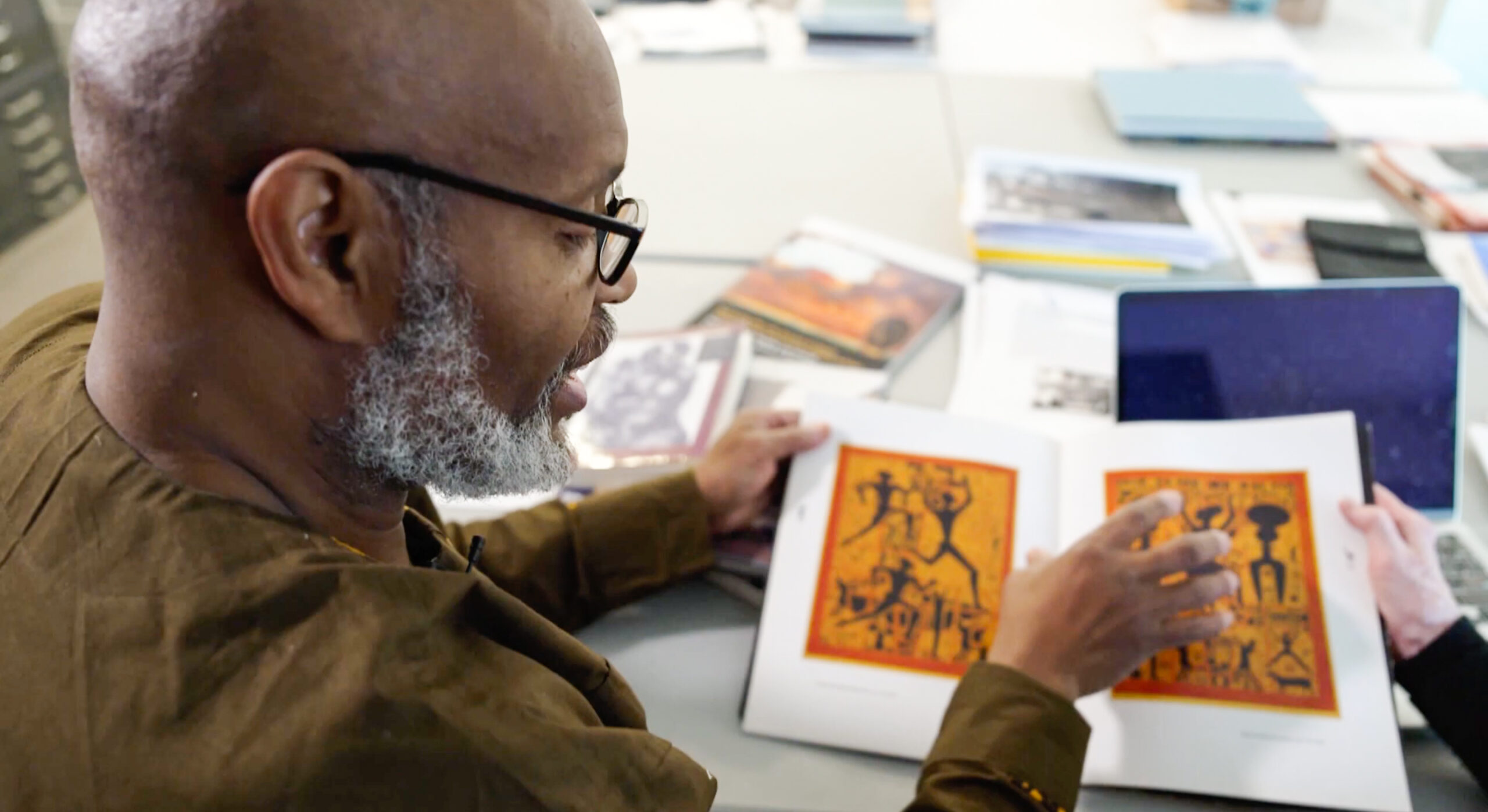

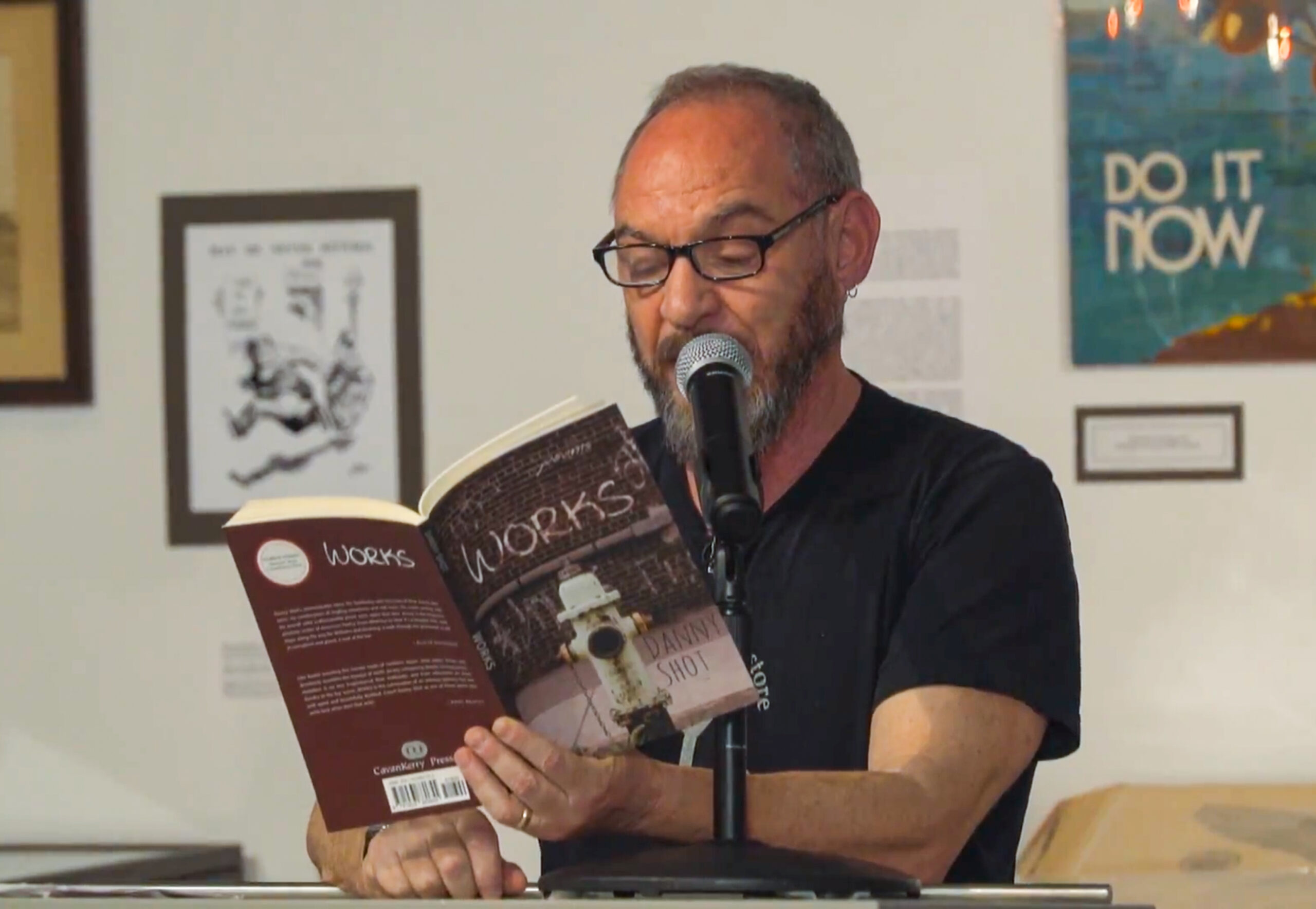

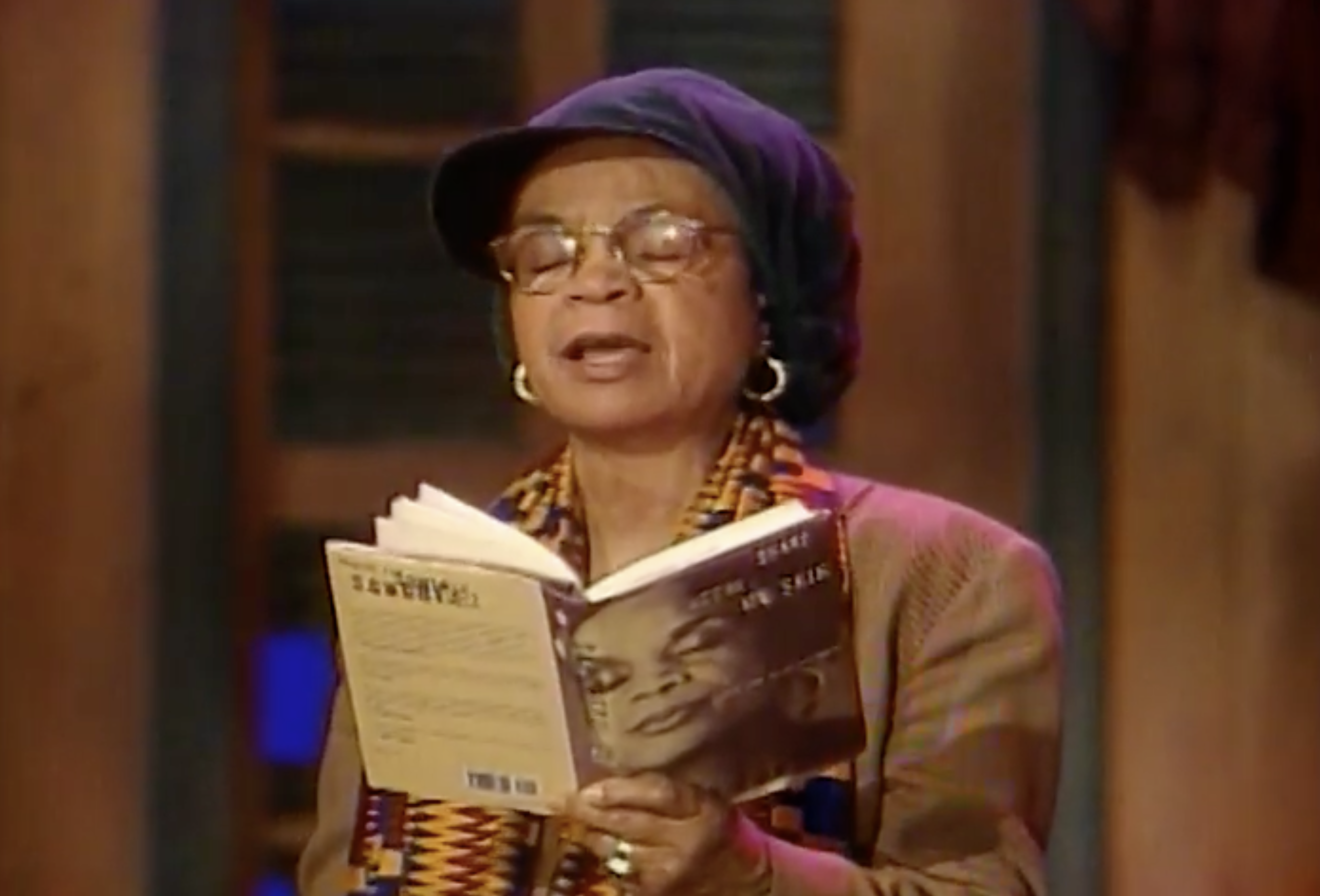

“I Might Be Next: Jerry Gant & Bryant Lebron,”

an exhibit at the Criminal Justice Gallery,

part of the Paul Robeson Galleries at Rutgers University- Newark.

Watch the State of the Arts story here.

Wonderful things about being black abound, from the physical to the cultural to the social.

Blackness is beautiful in the body, the skin, the vigor that shows in muscle and sinew. (Let us

here praise Serena Williams.) Beauty in the music and the poetry and the art. (Let us here

praise 2Pac and Duke Ellington and Elizabeth Alexander and Kara Walker and Stanley Whitney.)

And the beautifully almost un‐American sense of solidarity.

I want to talk about solidarity, as Bryant Lebron depicts it, and solidarity as Jerry Gant depicts

the sadness when it is missed.

That sense of community—of solidarity, of being connected over time and space and even

clashingly different experiences—distinguishes Americans of African descent from the

mainstream loudly proclaiming its individualism, stony, self‐reliant individualism. But we who

have been so persistently lumped together, discriminated against, even beaten as embodiments

of a group, have long embraced our group identity. Solidarity has been our talisman, our key to

sanity within an insane system of racial denigration. Where would we be without our peers to

reassure us that we were not insane? How to survive as an isolated individual, when

individualism would condemn a single person to insanity. No, individualism does not serve us

when we are mistreated as part of a group. Solidarity has saved the sanity of most of us, even

though legions have fallen victim to racism’s insanity.

In these times, the weekly drumbeat of murder turns solidarity into an endlessly renewed grief,

as a person is killed as each week goes by. We may be personally safe. But our solidarity

connects us, week by week, to each murdered black person. “That could have been me,” we

feel, we say, each time another loses her or his life senselessly. This cruelty stretches back

farther than Bryant Lebron says. In my mid‐twentieth‐century generation, it was the vicious

torture‐murder‐drowning of Emmett Till in 1955. Then it was the three young men in Freedom

Summer of 1964. The Black Panther Party for Self‐Defense began in 1966 to combat anti‐black

police brutality. Each of the urban uprisings of the twentieth‐century began with the fact or

rumor of police brutality. In each instance, we mourn the victims in racial solidarity and in the

knowledge that it could have been me. It could have been me, walking down the street in a

hoodie with Skittles in my hand. It could have been me avoiding the overgrown sidewalk. It

could have been me in the dark stairway or in the street selling loose cigarettes. It even could

have been me inviting the stranger into our prayer meeting. It could have been me changing

lanes without signaling and smoking in my car. Yes. In solidarity, I know it could have been me.

Nell Painter, Newark, New Jersey, July 2015