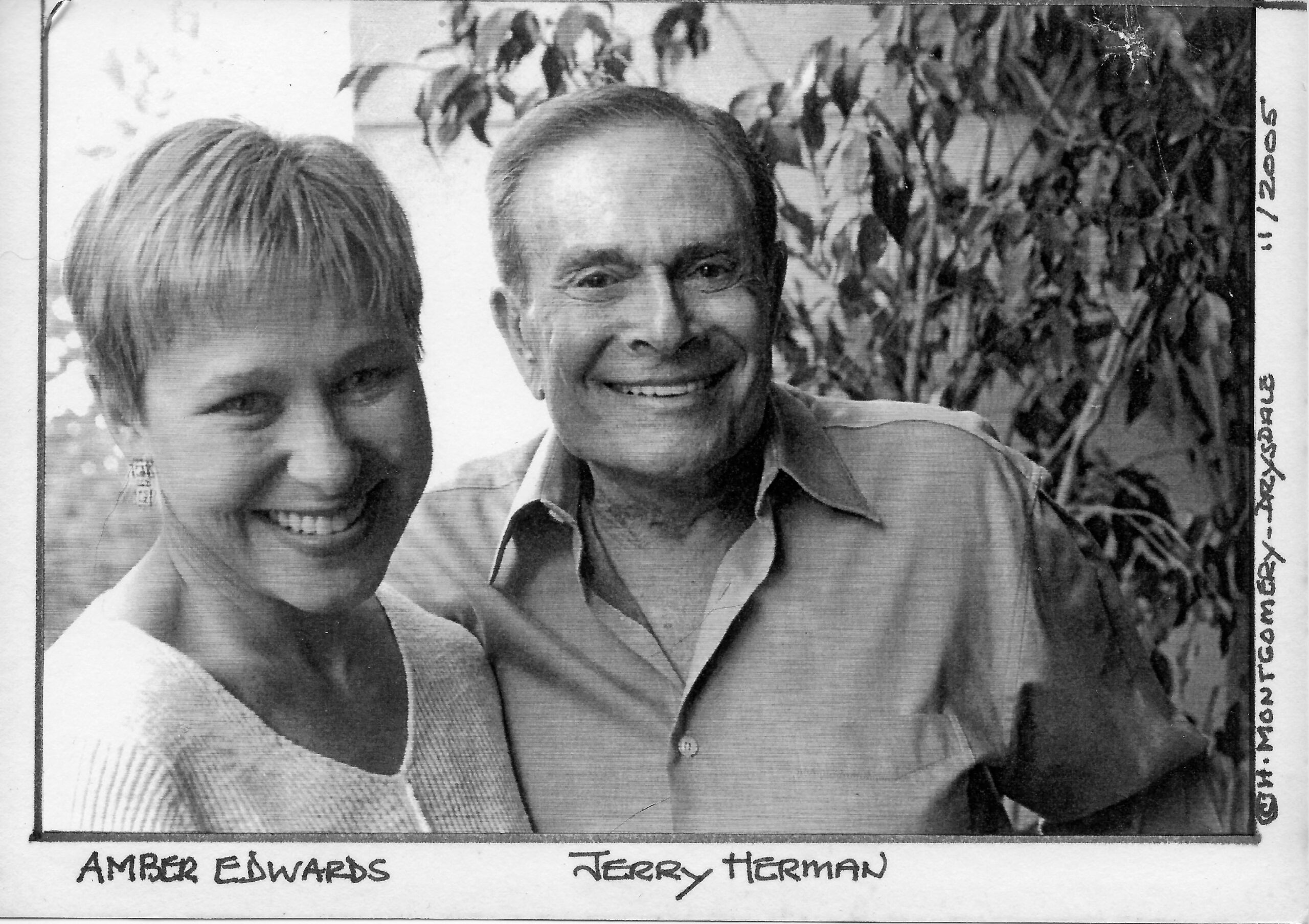

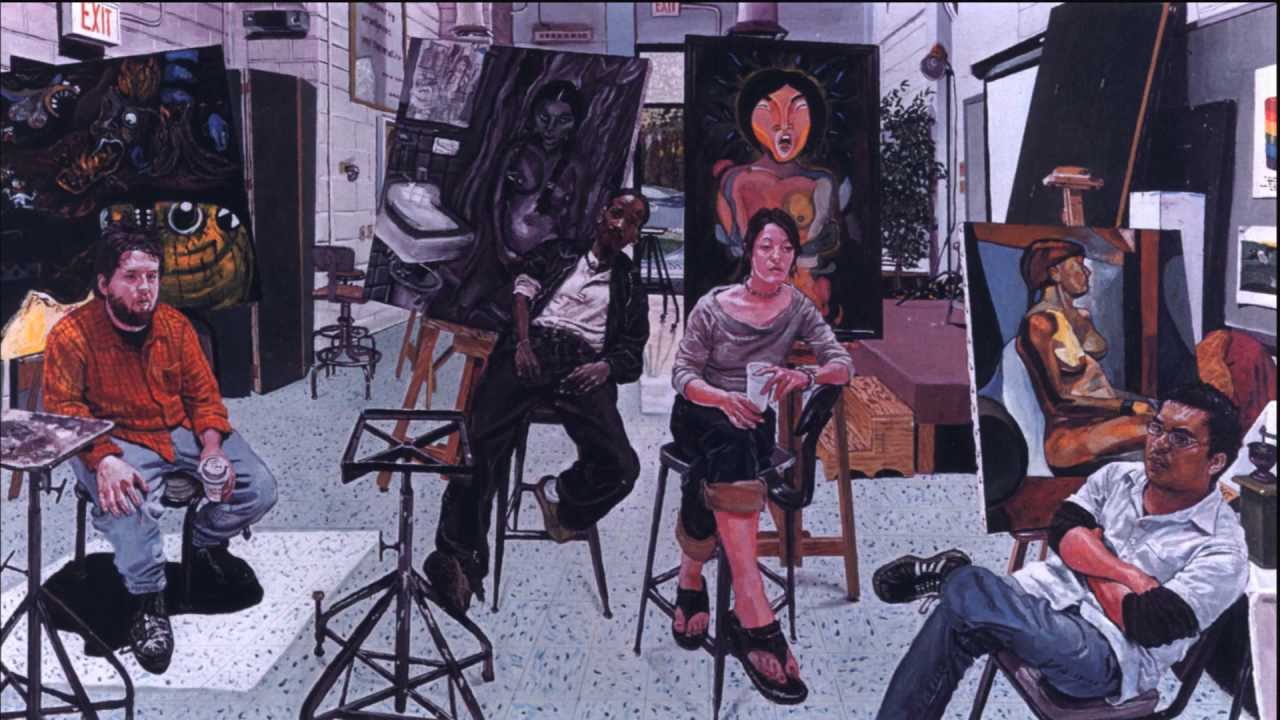

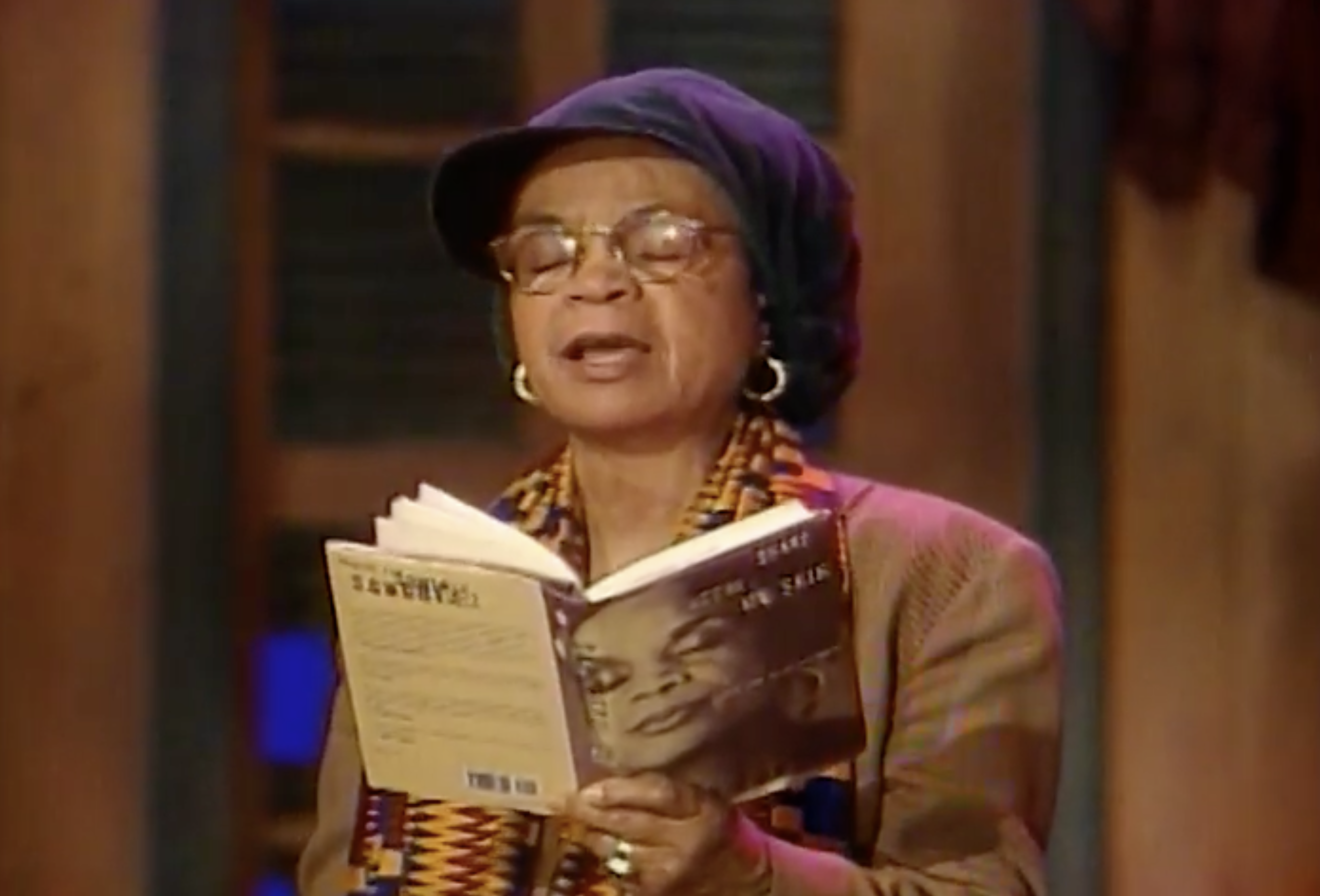

Amber Edwards and Jerry Herman in 2005 | Photo Credit: Helen Montgomery-Drysdale

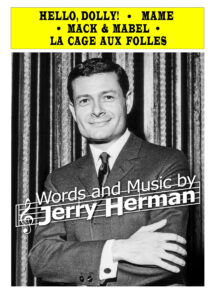

Showing the rough cut of a documentary to the documentary’s subject is fraught under any circumstances. When the subject happens to be a Broadway legend who has opened his archive, his Rolodex, and his heart to the filmmaker for the past five years the experience is stomach-clenching. And this was back in the day before celebrity “documentaries” were engineered, micro-managed, and paid for by the celebrity subject themselves. Jerry Herman had no say over the final cut of Words and Music by Jerry Herman, which had already been accepted for national PBS broadcast and would be scheduled once I turned in the fine cut.

We sat in his Beverly Hills study in front of a large TV screen, Jerry Herman and his partner Terry Marler and me, and for 90 minutes I watched Jerry out of the corner of my eye as he took in my telling of his life and career. He emitted a few inscrutable syllables—“oh”, “hmmm”, “ha”, and most mysteriously, “wow.”

After the credits rolled he said “It’s wonderful. Come back tomorrow and we’ll talk more.”

The next day, Jerry greeted me with a yellow legal pad and a kind smile. He started at the top of his list with “you got the wrong grandmother; it was my mother’s mother who lived with us, not my father’s.” He handed me a copy of a photo of the right grandmother—who looked much more like the jolly lady he had described in the documentary.

He then gave me a master class in showmanship. “You’ll get a laugh here, so hold the shot for another beat so the laughter doesn’t step on the next line.” “This moment would be funnier if you cut away sooner.” And, in a heartbreaking section on how AIDS ravaged the cast of La Cage Aux Folles, “Don’t be afraid to linger on this picture in total silence; let the audience absorb the fact that half of these young guys died during the run of the show.”

His last note was about the music I had chosen for the credits—a wistful, slow version of “Hello, Dolly”, played by Jerry himself, one of a dozen of his songs he had recorded for me as solo piano pieces I could use as underscoring throughout. “I know this is my most famous song, but it sounds like I’m already dead.” He was right, it was too lugubrious. “You want the audience to leave the theater happy, singing, and telling their friends what they’ve seen.” Of course, I replied; did he have anything in mind?

Jerry whipped out of his pocket a CD of symphonic arrangements from all his biggest shows, and pointed at Track 6, “The Best of Times”. The old showman was absolutely right, as he had been right about every single tweak. He was looking at this film as a piece of theater, and polishing it to a high gleam—in the service of the work, not his own ego.

When the film began a round of live preview screenings prior to the January 1, 2008 PBS broadcast, I saw firsthand the wisdom in each of his suggestions. People did indeed laugh out loud, and applaud after musical numbers, and weep in stunned silence. Jerry himself attended many of these events—at the Kennedy Center, the 92nd Street Y, and the Museum of Television and Broadcasting (now The Paley Center)—and I suspect that if the film hadn’t been locked by then, he would have had additional suggestions for micro-improvements. And I would have happily taken them.

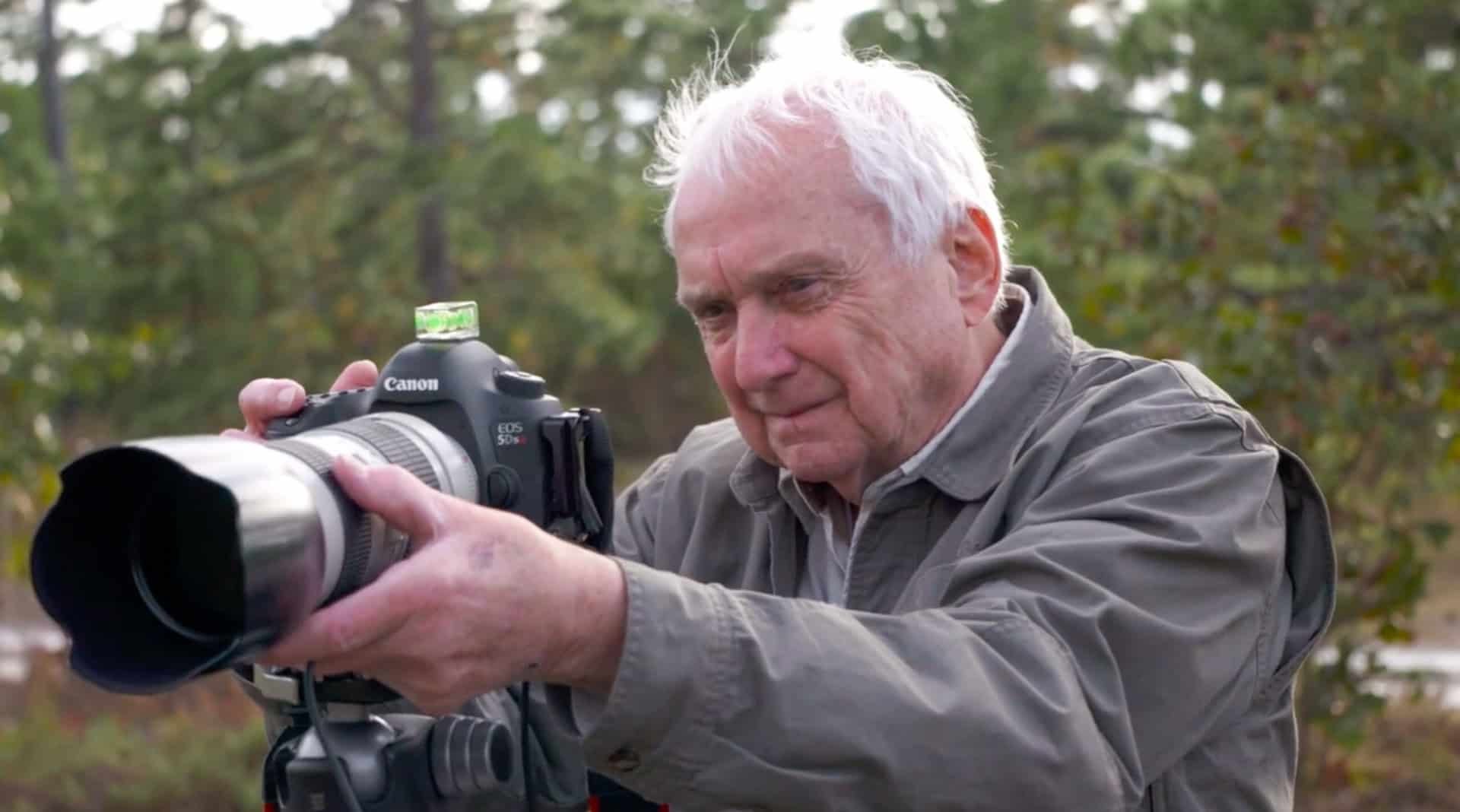

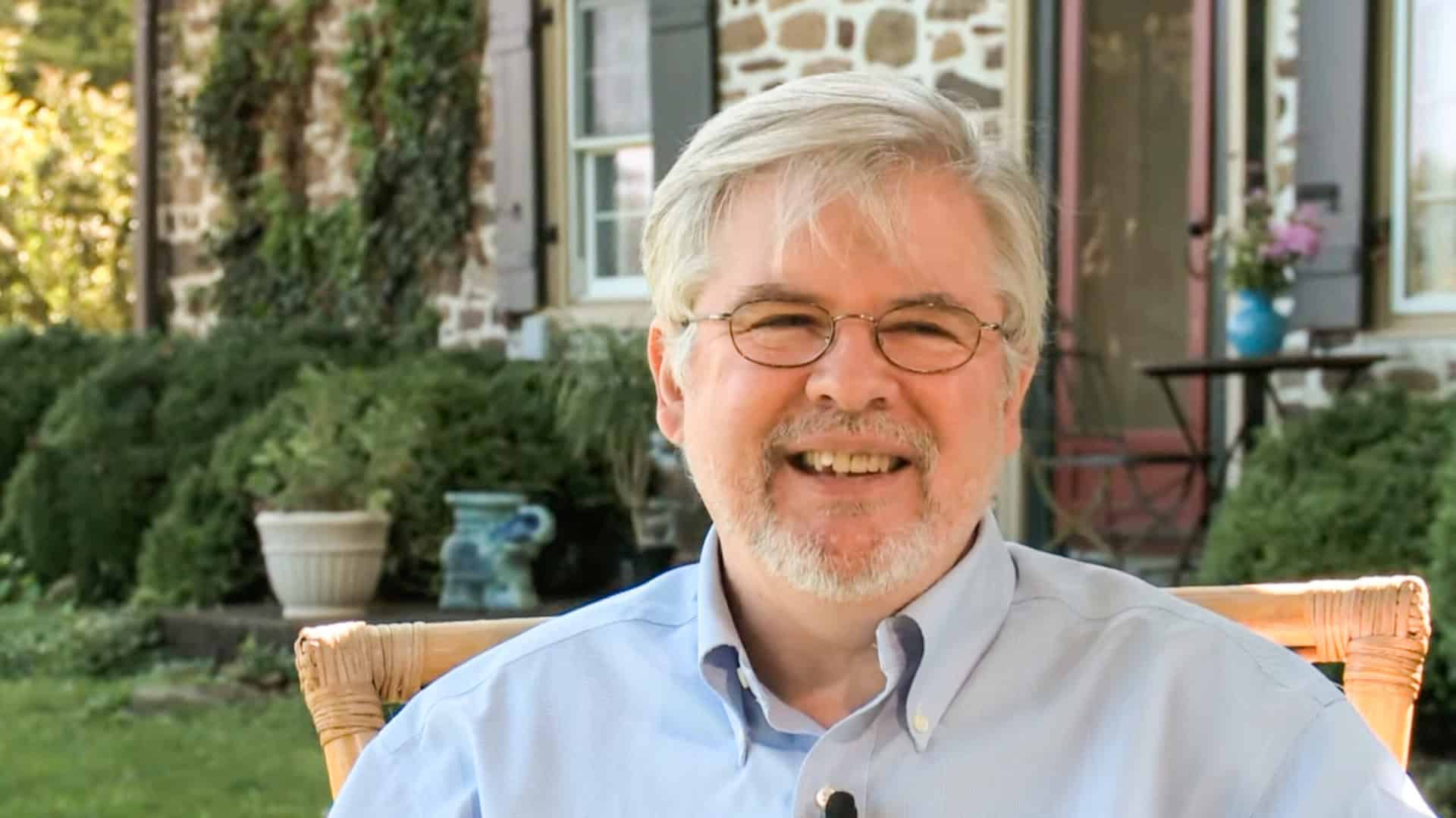

I must mention the archival footage in this documentary. Most of Jerry’s Broadway shows ran before it was customary to capture the performances on film or video—even for archival purposes. Hunting down moving pictures of these performances introduced me to an underground network of collectors and theater lovers who had managed to preserve this valuable history by hook or by crook. Two heroes come to mind: the prodigious film collector Fred MacDonald, who had among his treasures a half-hour television program of the college musical Jerry had written as a student at the University of Miami (!); and Jerry’s longtime music director, arranger, conductor, and friend Don Pippin, who would pass his baton to his assistant and race up to the mezzanine with his Bolex to shoot 8 mm films of the final dress rehearsals of Mame and Dear World. Although the films were silent, they could be synched with the original cast recordings; Don’s tempos were so consistent that I hardly had to make any adjustments.

The five years that I worked on this film were golden in so many ways: the key players in Jerry’s life and career were still alive and vigorous; I had unstinting support from New Jersey Public Broadcasting to “go big” with a national documentary about a Jersey City native—led by State of the Arts’ unflappable Executive Producer Nila Aronow; and PBS was still the unchallenged gold standard of arts and history programming. As Jerry Herman would say, “timing is everything.”

I am overjoyed that, on the occasion of what would have been his 93rd birthday, this film portrait is “back where it belongs,” in front of the public.

Amber Edwards

Producer/Director/Writer/Editor