I met the concert pianist Vladimir Feltsman in May of 1990 in the course of producing a State of the Arts feature. At the time, his notoriety as a Soviet refusenik nearly eclipsed his fame as a classical virtuoso. A year later, he contacted me with an irresistible offer: travel to the USSR and make a documentary about his first performance in his homeland since his arrival in the USA in 1987. The concert was being organized by a brash independent impresario, Boris Rozin, as a poke in the eye to the Soviet Ministry of Culture — which had officially silenced Feltsman for eight years before he was allowed to emigrate.

The concert was to take place in the legendary Moscow Conservatory in October of 1991, which happened to be just two months before the Soviet Union would collapse. It was a period of extraordinary deprivation for the Soviet citizenry, with shortages of everything from food to clothing to petrol to cigarettes. Whenever people saw a line form they joined it—in desperate need of anything that was briefly available for purchase.

Impresario Rozin had arranged my lodging (I was housed in one of those enormous spaceship-like concrete slab hotels, where I enjoyed the scrutiny of a scowling babushka “hall matron” who searched my room daily,) meals, transportation, a translator, and a Soviet camera crew. I merely had to provide the videotape stock. I stepped off the plane in Moscow lugging two suitcases filled with one-hundred spanking new BetaSP tapes, the state-of-the-art broadcast format of the 1990s.

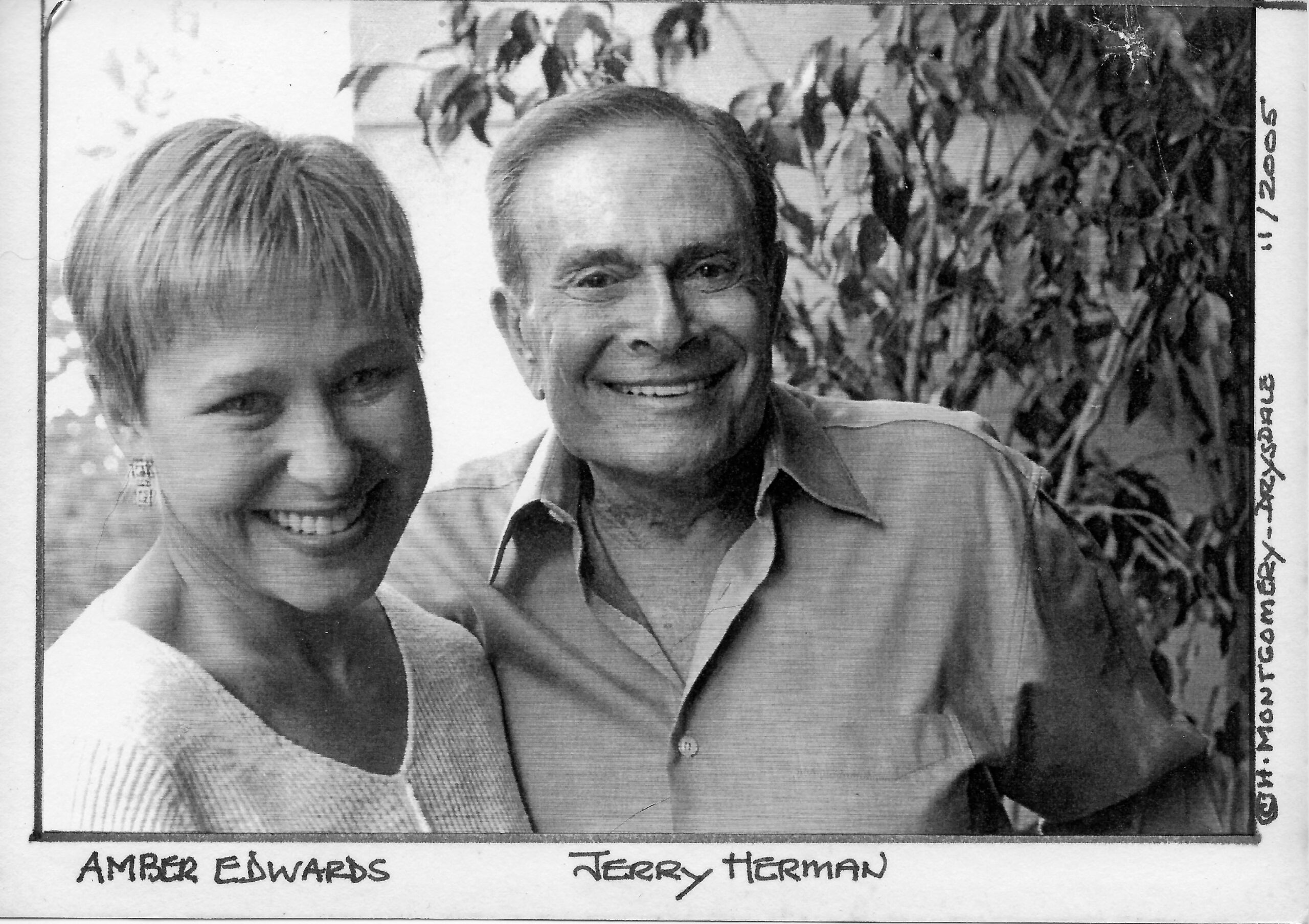

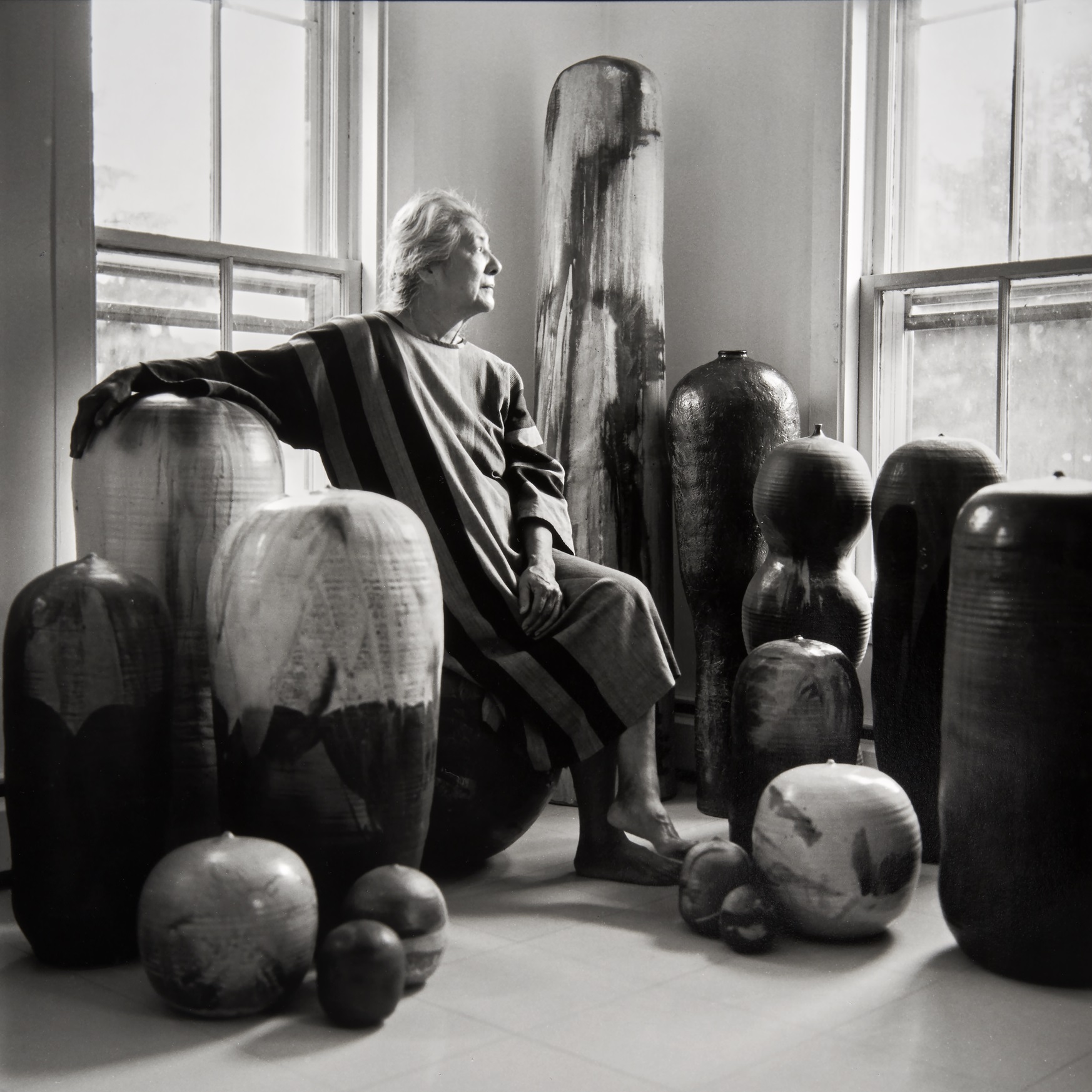

Producer Amber Edwards, now of Hudson West Productions

Feltsman’s return was a big enough story that CBS sent a “Sunday Morning” producer and two-person crew, who were friendly and professional and regarded my Soviet crew with considerable bemusement—as did I. I had been issued eight people: a van driver, two “Lamp Man” (lighting;) two “Microphone Man” (audio;) my translator Andrey; an unsmiling woman “monitor” (my KGB minder;) and my skilled cameraman, Alexi, who practiced every shot before he turned on the camera, to save videotape. (He had never seen so many brand new Sony cassettes and regarded each one as precious.)

When I questioned why multiple people were doing identical jobs, my translator Andrey explained that each crew member had his own piece of equipment which could not be shared. So Microphone Man #1 operated a boom mic and nothing else, and Microphone Man #2 was in charge of the lavaliere mic and nothing else. Every morning, the Microphone Men would ask me if I would be needing any audio today. “Da,” I would nod. “When?” “All day.” (It was, after all, a documentary about a musician, making audio a significant element.) When I asked Andrey about this (the same queries also came from the Lamp Men—#1 in charge of standing lights, #2 in charge of handheld— Andrey informed me that in the USSR it was customary for all workers to take several hours off during the workday in order to stand in line for shoes or sausages.

Granting my crew no free time for shopping, I filmed Feltsman all over Moscow for six days prior to the concert: at home with his parents, visiting the family dacha, being interviewed on Soviet State TV, shopping on the Arbat, giving master classes. Because I had no tape deck to review the footage we shot every day, I made Boris promise that he would personally take the tapes to a TV studio every night and watch and listen to every single one, to be sure we had gotten what we thought we had.

The morning after the big concert (which was recorded and broadcast live on Soviet State television), Boris came to me in a panic.

“Camera is broken,” he said.

“Well, we’ll have to rent another one for today,” I replied.

“No, camera has been broken. Since yesterday.”

“During the concert?”

I was now the one in a panic.

Boris had been too exhausted to check the tapes from the previous night, which would have revealed the problem in time to act. But the problem was all mine now. The big event I had traveled to capture had not been captured.

But, I realized, it had—by the CBS crew, who kindly offered to share their footage once their story had aired, and by the Soviet TV station, which Boris successfully bribed to turn over their master tapes to me.

My luggage now filled with precious cassettes and my mind reeling from my week in Moscow, I flew home on what would be the very last Pan Am Airlines international flight from Paris before it ceased operations and declared bankruptcy. For some reason I will never know, I was upgraded to first class.

Can we ever predict the end of the era that we are living in?