Did you know that the largest collection of post-WWII Soviet Art is found in New Jersey, at the Zimmerli Art Museum of Rutgers University?

As Russia today tightens control over free speech, it raises the spectre of the oppression experienced by artists in Soviet times. Our recent profile of the duo Komar and Melamid, who met in art school and became perhaps the most famous dissident artists of the Soviet era, brings that time vividly to life. “What [the Soviet Union] was afraid of was the imagination, and not being taken as seriously as they took themselves. That’s the particular crime that Komar and Melamid committed,” says curator and artist Robert Storr.

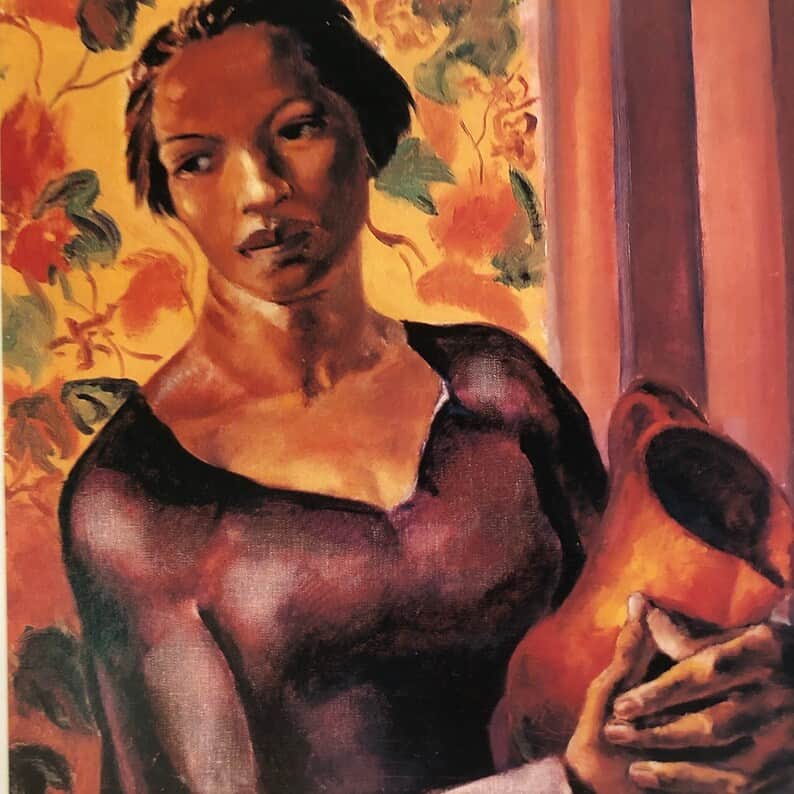

Komar and Melamid are among the most famous, but many artists in the Soviet Union suffered repression and censorship. Their art, and their stories, are the focus of the largest collection of Soviet dissident art found anywhere, the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Soviet Nonconformist Art at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

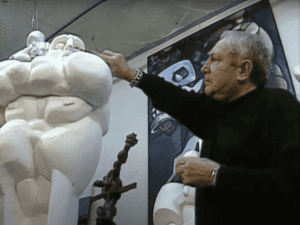

During the Cold War, economist and educator Norton Dodge smuggled thousands of artworks out of the Soviet Union. These were artworks that were not approved by the regime, whether or not they were political in theme. Sculptor Ernst Neizvestny, for instance, did not consider himself to be a dissident artist—in fact, he didn’t create politically-motivated art at all, unlike many in his circle. “I was an underground artist only because I wanted to speak like a human being, like a person. Like Ernst Neizvestny,” he explains. “I was an outsider. Because I was an outsider, I was a dissident.”

Norton Dodge was a key part of the underground push to save artworks deemed unacceptable by USSR standards. In 1996, State of the Arts producer Marc Fields met Dodge, and produced a half-hour documentary about his remarkable efforts to save and preserve the work of dozens of nonconformist artists.

From Gulag to Glasnost tells the story of how dissident art was smuggled out of the Soviet Union—highlighting the clandestine effort to save thousands of aesthetically, historically, and socially important artworks. “These artists really believed that the art they were doing, though not explicitly political, would redeem people from the dehumanizing circumstance of life in a society dominated by ideology,” art critic Andrew Solomon explains. Norton Dodge’s collection of smuggled art is enormous—his efforts wound up amassing roughly 20,000 works created between 1956 and 1986.

Today we invite you into the State of the Arts archives for a look at the past, and its continuing echoes, with From Gulag to Glasnost and Komar and Melamid.

Mae Kellert

Communications Producer, State of the Arts